April 7, 2024 @ Richard Wall House

Discuss Science and see gear

1:00 – 4:00pm

and

April 8, 2024 @ Historic Rittenhouse Town

Actually SEE THE ECLIPSE!

1:00 – 4:00pm

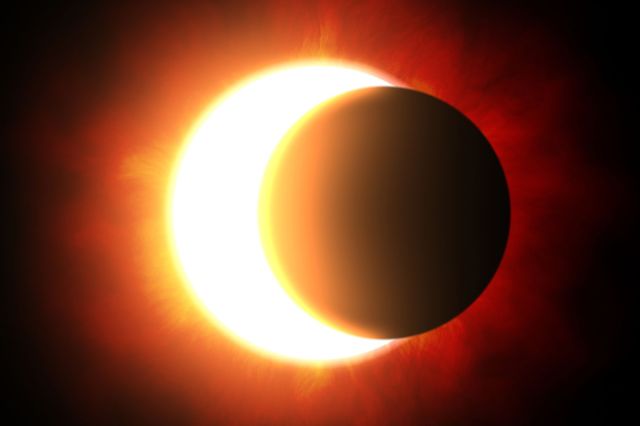

A solar eclipse occurs when the Moon passes between Earth and the Sun in such a manner that the Moon’s shadow sweeps over Earth’s surface. This shadow consists of two parts: the umbra, a cone into which no direct sunlight penetrates; and the penumbra, which is reached by light from only a part of the Sun’s disk. To an observer within the umbra, the Sun’s disk appears completely covered by the disk of the Moon. This is a total eclipse and on April 8th, 2024 people in western Pennsylvania and New York will be able to observe a total eclipse at about 1500 EDT. Observers within the penumbra, see a partial eclipse and the farther from the umbra the observer is the more of the sun’s disk remains visible. Fortunately, in Philadelphia, we are relatively close to the path of the umbra so we will experience about an 80% totality of eclipse. In a partial eclipse, the center of the Moon’s disk does not pass across the center of the Sun’s. At the moment of maximum eclipse, a crescent shaped shadow will be cast over the disk of the sun.

People have been alternatively amused and terrified by solar eclipses. According to Babylonian scholars, eclipses could foretell the death of the king. This belief was so pervasive that an alternative person would be chosen and dressed like the king then put upon the throne so that the real king would be spared and this imposter would receive the foretold fate. The real king would then keep a low profile and avoid being seen. If nothing happened to the imposter, the substitute king was put to death, therefore fulfilling the prophetic reading of the celestial omen while saving the life of the real king. This ritual would take place when an eclipse was predicted, something that ancient Babylonians became very well practiced in.

Mesopotamia was not unique in their fears of eclipses. A chronicle from of early China known as the “Bamboo Annals” (竹書紀年 Zhúshū Jìnián) refers to a total lunar eclipse that took place in 1059 BCE, during the reign of the last king of the Shang dynasty. This eclipse was regarded as a sign by a vassal king, Wen of the Zhou dynasty, to challenge his Shang overlord. The Pomo, an indigenous group of people who live in the northwestern United States, tell a story of a bear who started a fight with the Sun and took a bite out of it. In fact, the Pomo name for a solar eclipse translates to the “Sun got bit by a bear.” The ancient Greeks believed that a solar eclipse was a sign of angry gods and that it was the beginning of disasters and destruction. Many people around the world still see eclipses as evil omens that bring death, destruction, and disasters. Even today, there are popular misconceptions that solar eclipses can be a danger to pregnant women and their unborn children. In many parts of India, people fast during a solar eclipse due to the belief that any food cooked while an eclipse happens will be poisonous and unpure. Of course, none of these superstitions have any factual basis. This is why in 1715, when Edmond Halley published a map predicting the time and path of a coming solar eclipse over England, Halley wrote that if people understood what was happening when the Moon’s shadow passed over England “They will see that there is nothing in it more than Natural, and no more than the necessary result of the Motions of the Sun and Moon.”

Astronomers have studied the patterns of solar eclipses going back millennia and had some success in predicting their arrival. But as 18th-century astronomers sharpened their understanding of the solar system and the motion of the Earth, Moon, and planets, they were able to predict the paths of solar eclipses with unprecedented accuracy. Part of the reason that 18th-century scientists produced groundbreaking eclipse maps is that there were so many eclipses in this time period—two annular and five total solar eclipses in the British Isles alone, which is a greater frequency than normal.

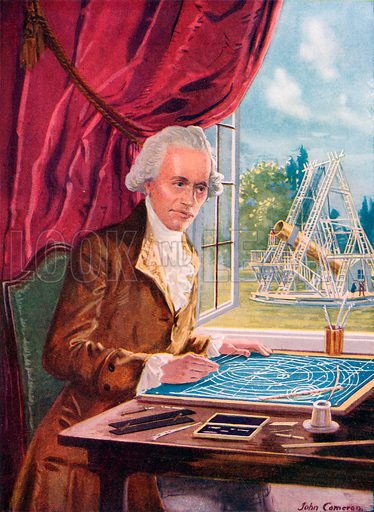

On our side of the Atlantic, the total solar eclipse of June 24, 1778 was carefully observed by David Rittenhouse from his observatory outside Philadelphia. Thomas Jefferson also tried to observe this eclipse but was frustrated by clouds in Virginia. The British Army had just evacuated Philadelphia on word that the French had entered the war. For years after, the eclipse would be remembered as portending victory for the Continental Army in the Battle of Monmouth, which took place two days after the eclipse.

Two years later on October 27, 1780, an eclipse expedition was sent from Harvard University into Penobscot Bay in Maine, deep behind British lines. The Royal Society and Parliament were so eager to have observations from this eclipse because it would allow observers to sharpen their measurements of longitude by computing the time difference with that of Greenwich. Uncertainty of longitude in almost all locations in America bedeviled the best geographers and mariners well into the early 19th century so these observations were of vital interest. Unfortunately, the best observers were not loyalist and the closest available team was in Boston (Harvard University). To make matters worse, Massachusetts militia and privateers had laid siege to the Fort George fort Penobscot Bay so special diplomatic passes had to be arranged. Massachusetts Speaker of the House John Hancock wrote a letter to the commander at Fort George asking for safe passage and permission to set up an observation site. Colonel Campbell, the commanding officer, gave them five days and insisted they stay off the mainland. Ultimately, Williams’ calculations were flawed. The location was off and he missed totality. However, what he observed improved navigation and was of strategic interests to both sides for decades after the war.

In 1789, Benjamin Banneker; the country’s first great African-American mathematician, astronomer and surveyor of the new federal city – Washington DC; published his first almanac. These almanacs were so accurate that they were used by the United States Naval Observatory. Banneker used a method known as “the conversion of eclipse cycles.” This method allowed him to predict eclipses years in advance. This method for predicting solar and lunar eclipses is so accurate that it is still used by astronomers today. On the day of the solar eclipse, April 8, 1789, the day of a total solar eclipse, Banneker invited President George Washington and several prominent guests to his home outside Baltimore for a dinner party to view the event.

Every agriculturally based civilization developed a calendaring system so that they could predict the best time for planting. The most ubiquitous of these were based on the cycles of the moon and before long, people began to notice patterns. One of the clearest patterns for predicting solar eclipses is the Saros cycle, first observed by the ancient Mesopotamians. Within a Saros series, solar eclipses occur at intervals of 223 lunar months. Unfortunately, the subsequent Saros eclipses don’t happen in the same place, but one-third of the way around the Earth. It takes three Saros cycles for an eclipse to recur in a similar place as the first one—approximately 54 years later and that instance might occur night and be unobservable but the system works. Another problem with the Saros cycle is that multiple cycles occur at the same time. In North America, we saw an eclipse in 2017 eclipse and will see other (in a different cycle) on April 8, 2024. Given that there are about 40 of these cycles taking place at any given time, and each last for about 1,000 years, it’s hard to tell which is part of which pattern without detailed recordkeeping like an almanack.

Another way to predict eclipses is to build a machine that mimics the movements (and the axial tilt) of the earth and moon orbiting the sun. An orrery is a mechanical model of the Solar System that illustrates or predicts the relative positions and motions of the planets and moons. The first accurate orrery was produced in 1713 by Charles Boyle, 4th Earl of Orrery – hence the name. These machines are typically driven by a clockwork mechanism with a globe representing the Sun at the center, and with planets at the end of clockwork driven arms. Moons (when present) then revolve around these planets. As a clockmaker, David Rittenhouse completed an advanced orrery in 1770, that earned him an honorary degree from the College of New Jersey. There were, other attempts to make these models in the past but all were stymied by the issues of scale. The actual size of the solar system (and hence the proportional sizes of the planets and their orbitals) was not fully understood until the Astronomical Unit was calculated following the detailed observations of the Transit of Venus in 1769.

Today we rely on mathematics. Determining when and where an eclipse will occur is really just a matter of geometry. The math is not necessarily hard, but there’s a lot of it. You compute the motion of the Moon’s shadow on a plane that crosses the Earth’s center. This gives us a “shadow cone” can be projected onto the Earth’s surface. To define the Besselian elements of an eclipse, a plane is passed through the center of Earth which is fixed perpendicular to axis of the lunar shadow. This is called the fundamental plane and on it is constructed an X-Y rectangular coordinate system with its origin at the geocenter. The axes of this system are oriented with north in the positive Y direction and east in the positive X direction. The Z axis is perpendicular to the fundamental plane and parallel to the shadow axis. The X-Y coordinates of the shadow axis can now be expressed in units of the equatorial radius of Earth. There are eight parameters plus time so this is a laborious technique really only practical with a computer to crunch the numbers.

On April 7th, in his personae as David Rittenhouse, the Regimental Brewmeister will assemble an observatory at the Richard Wall House in Cheltenham, Pennsylvania. We will not be able to observe the eclipse yet but you can come out and discuss the science and learn how Rittenhouse made his observations of the transit of Venus (a similar phenomenon where Venus passes between the Sun and the Earth) in 1769 and of the Solar Eclipse in Philadelphia in 1778. We will also discuss why these measurements were so important that the Revolutionary War was briefly suspended to allow Rittenhouse and his team to safely accomplish these observations. On April 8th, we will assemble the observatory again at David Rittenhouse’s childhood home in Germantown. This is a momentous occasion because not only will we get to actually observe, using period equipment, the solar eclipse but we get to do this on David Rittenhouse’s birthday.

You must be careful when viewing an eclipse. One should never look directly at the sun, especially with a telescope as this can lead to solar retinopathy, a condition where the intense UV light literally burns a hole in the retinal tissues. UV radiation from the Sun can destroy the rods and cones of the retina and can create small blind spots. What’s worse is that because the retina does not have any pain-receptors, so you won’t feel the damage being done.

We will be arranging to have solar filter glasses available for people at Rittenhouse Town this year. These special glasses are EXTREMELY dark and filter out 95% of the sunlight and all of the UVA/UVB radiation. With these you CAN look at the sun but only for short periods of time. The problem with filters is that as the eclipse progresses, it will get darker. As it gets darker, your pupils dilate to let in more light and then… the eclipse begins to wane and you are staring into the bright ball of the sun. So, you can use these but that is not the method Dr Rittenhouse will be using.

We will be using our telescopes but observing the eclipse INDIRECTLY. The telescope lets us get a bigger image which we will then project onto a piece of paper. As the eclipse progresses, we can trace the image for later analysis. This solar-projection method is the same method Dr Rittenhouse’s team used to watch the Transit of Venus in 1769 as a surprising amount of detail on the solar surface can be seen, including sunspots and flares (even when there is no eclipse. Since we are not looking directly into the sun, as the eclipse wains, our eyes are not directly exposed to the burst of UV radiation even though our pupils will dilate.

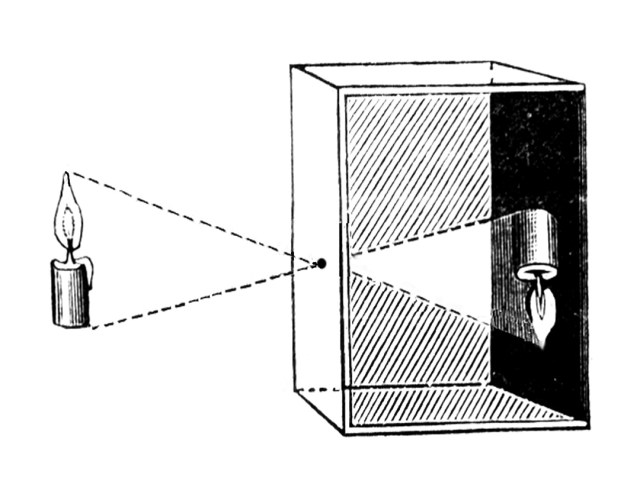

Another great way to view the eclipse indirectly is to use a simple pinhole camera. This simple device allows you to view the eclipse indirectly by casting a shadow of the sun onto another surface in much the same way our telescope will project the sun but with less magnification. A pinhole camera is a simple camera without a lens but with a tiny aperture (the so-called pinhole) over a light-proof box. Light passes through the aperture and projects an inverted image on the opposite side of the box. The size of the images depends on the distance between the object and the pinhole. We will assist those of you who wish to build these. Please bring a small box.

Want to have the

Regimental Brewmeister

at your site or event?

You can hire me.

https://colonialbrewer.com/yes-you-can-hire-me-for-your-event-or-site/