Benjamin Banneker was born free in 1731 in Baltimore County, Maryland. He was gifted in the sciences and became a naturalist and almanac-maker. Banneker lived near the Ellicott family gristmills, and Andrew Ellicott’s cousin had encouraged Banneker’s talent for computing. These talents ultimately led to his being a critical part of the team that did the surveys for the new federal District of Columbia which would become our new capitol.

American supporters of slavery tried to justify their holding and mistreatment of slaves with the pseudoscientific arguments of David Hume “I am apt to suspect the negroes, and in general all other species of men (for there are four or five different kinds) to be naturally inferior to the whites.” Such reasoning arose not from empirical observation or science but rather traditional Christian beliefs of common descent from a divinely created first human pair. To the traditional European Christian establishment, men who looked like them must be the descendants of Adam (Genesis Chapter 2). Black men, they argued must have evolved from apes and baboons as a single species of Africans. Jefferson, for all his high-minded rhetoric about equality, publicly endorsed Hume’s ideas of polygenism (the belief in the separate creation of the various races or species of people). But Banecker stood as direct refutation of Hume’s argument. Here was a self-taught man who was the intellectual rival of the best mathematicians in the world and clearly a much more talented scientist than Jefferson.

Abolitionists knew that in order to apply the promise of “all men are created equal” they had to disprove Hume’s (and hence Jefferson’s) argument that the African race are not men. Princeton theologian Samuel Stanhope Smith, took aim at polygenism in a 1787 address to Philadelphia’s American Philosophical Society published under the title An Essay on the Causes of Variety of Complexion and Figure in the Human Species. Marshalling far more observations of human types than Jefferson ever mustered, Smith defended the biblical “doctrine of one race” by arguing that skin color and other racial traits derive solely from environmental causes, primarily heat and sunlight, with black being “the tropical hue.” Moreover, these superficial traits remain mutable. Africans removed to a temperate climate already exhibited some physical transition, Smith claimed. Like all the bigots that followed, Jefferson came up with counter-arguments and when these failed, simply dismissed the arguments as spurious.

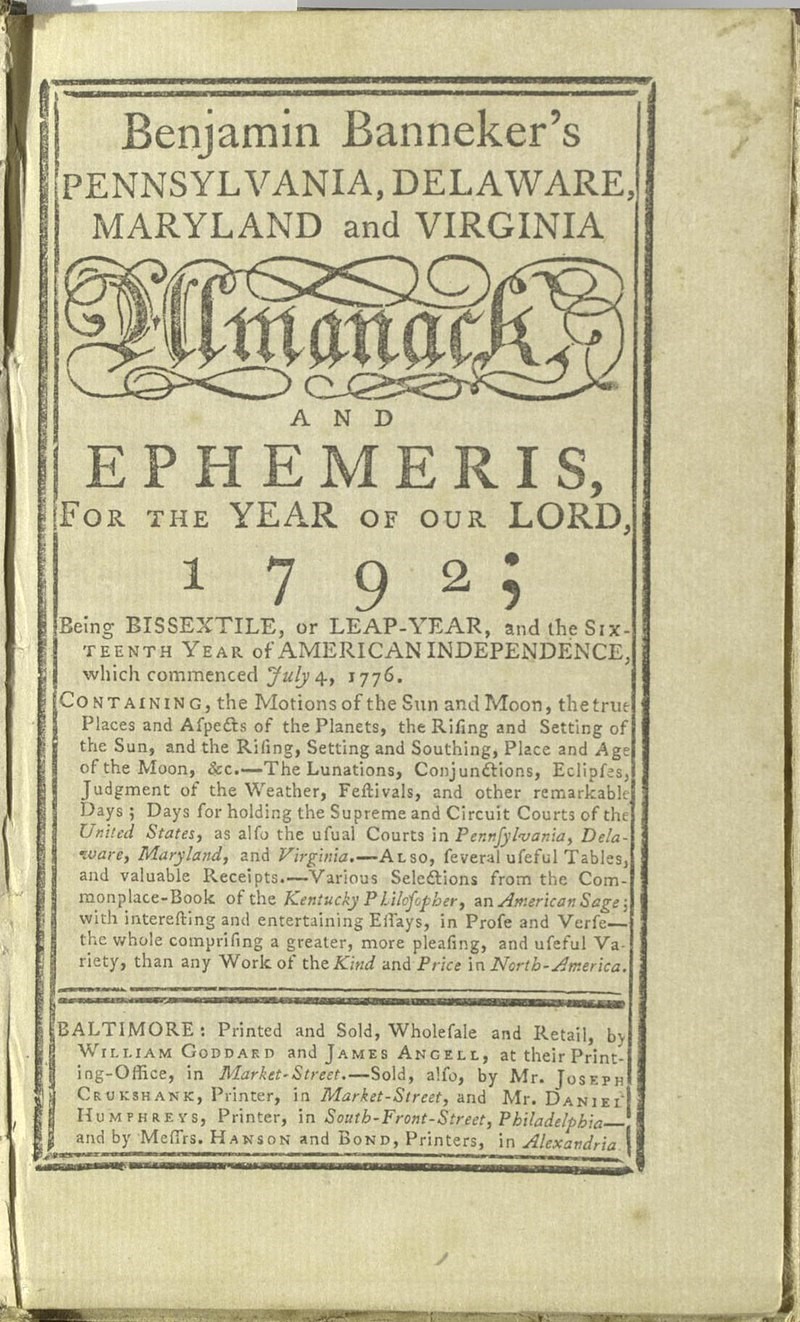

Then Benjamin Banneker published his astronomical calculations in an almanac of 1792. Banneker’s skill in computing celestial phenomena were on a par with the work of Isaac Newton. Making these tables took skill but, at a time when people relied almost exclusively on the sun and moon for light, and farming and fishing remained principal vocations, these specific calculations had practical value. Farmers used them to plant and harvest crops, travelers used them for planning night-time trips, and because tides rise and fall with the gravitational pull of the sun and moon navigators used them for sailing oceans and bays. The local time for the rising and setting of the sun and moon, tides, eclipses, and the like varied over the year, based on the observer’s longitude and latitude. Creating these tables, in an era without modern computing was a huge and complex task, and here was Benjamin Banneker, a self-educated, black freeman in Baltimore doing it to a precision that was on a par with the best astronomers and physicist in the world. Clearly advanced intellect was not the sole purview of white men.

Andrew Ellicott; an abolitionist, Quaker, and long supporter of Benjamin Banneker; suggested that Banneker send an advance copy to Jefferson as an example of a Black person’s faculty of reason. Ellicott went on to pen the introduction to the first edition and hailed it as “an extraordinary Effort of Genius by a sable Descendant of Africa, who, by this Specimen of Ingenuity, evinces, to Demonstration, that mental Powers and Endowments are not the exclusive Excellence of white People.” This preface included testimony to the accuracy of Banneker’s calculations from the David Rittenhouse, as “second to no astronomer living.”

In August 1791, Banneker sent a handwritten copy to Secretary of State Jefferson with a cover letter making his case for the right of blacks to liberty: “We are a race of Beings who have long labored under the abuse and censure of the world, and have long been considered rather as brutish than human, and Scarcely capable of mental endowments. Having heard that you are a man far less inflexible in Sentiments of this nature, than many others,I apprehend you will readily embrace every opportunity to eradicate that train of absurd and false opinions which so generally prevails with respect to us.” Banneker then made his case for universal liberty and abolition of slavery: “Sir, Suffer me to recall to your mind that time in which the Arms and tyranny of the British Crown were exerted with every powerful effort in order to reduce you to a State of Servitude. This Sir, was a time in which you clearly saw into the injustice of a State of Slavery, and publickly held forth this true and invaluable doctrine, which is worthy to be recorded and remember’d in all Succeeding ages. ‘We hold these truths to be Self-evident, that all men are created equal, and that they are endowed by their creator with certain unalienable rights, that among these are life, liberty, and the pursuit of happyness.‘”

Within ten days of receiving Banneker’s letter, Jefferson replied with a courteous four-sentence note. “No body wishes more than I do to see proofs as you exhibit, that nature has given to our black brethren, talents equal to those of the other colors of men, I consider it as a document to which your whole color had a right for their justification against the doubts which have been entertained of them.”

Abolitionists promptly published this exchange, but it did not alter Jefferson’s behavior. He persisted in holding people in slavery and, as president, defended state-sanctioned slavery. The supposedly scientific debate over monogenism versus polygenism intensified in antebellum America with the spread of slavery in the South and Southwest and the rise of abolitionism in the North and Midwest. As a rule, anti-slavery scholars took one side; pro-slavery scholars took the other. Polarization over the issue reigned in American science as much as it did over slavery in American society. This polarization eventually led to the Civil War and later abuses on Americans of African descent and is a critical part of today’s “red state/blue state” feud. When will be accept that “all men are created equal and endowed by their creator with certain unalienable rights…”?

Want to have the

Regimental Brewmeister

at your site or event?

You can hire me.

https://colonialbrewer.com/yes-you-can-hire-me-for-your-event-or-site/