When Vice President Aaron Burr killed Alexander Hamilton in a duel in 1804, he also killed his chance to be president. Wanted for murder in New York, he fled the state and went to Philadelphia. Realizing that he had no future on the east coast, Burr, in a frantic effort to salvage his destroyed political power and heavily in debt, conceived a plan to seek political fortunes beyond the Alleghenies. Burr’s scheme was to organize a revolution in the West, take the Ohio and Mississippi Valleys and form them into a separate republic. He also conspired to establish a republic bordering the United States by seizing Spanish possessions in Louisiana and Texas. To gain support for his plans, Burr approached British Minister, Anthony Merry, living in Philadelphia, and offered to help Great Britian regain control over the Western United States. He also contacted his old friend, General James Wilkinson, who had served with Burr during Benedict Arnold’s raid into Quebec.

Conspiracy and intrigue were not new to Burr and Wilkinson. Both rose rapidly through the ranks of the Continental Army. Both supported General Horatio Gates and the Conway Cabal designed to replace George Washington as commander-in-chief with Gates. Both aspired to high office following the Revolution. It was the “Burr Conspiracy,” however, that finally ended the career of these miscreants.

We all know of the rivalry between John Adams and Thomas Jefferson in the hotly contested election of 1800. Often overlooked, however, is the fact that Jefferson did ont win this election outright. Instead, because of the way the ticket was placed on the ballet, Jefferson and Arron Burr won an equal number of Electoral College votes in the 1800 focing the presidential election to be decided by the US House of Representatives. Thomas Jefferson was elected President and Burr was elected Vice President. Burr, however, was convinced he was cheated (by Alexander Hamilton who lobbied against him). Because of this animosity, Burr was largely ineffective as vice president and generally ignored by President Jefferson, who suspected that he had made secret deals with some Congressmen in attempts to secure the presidency for himself.

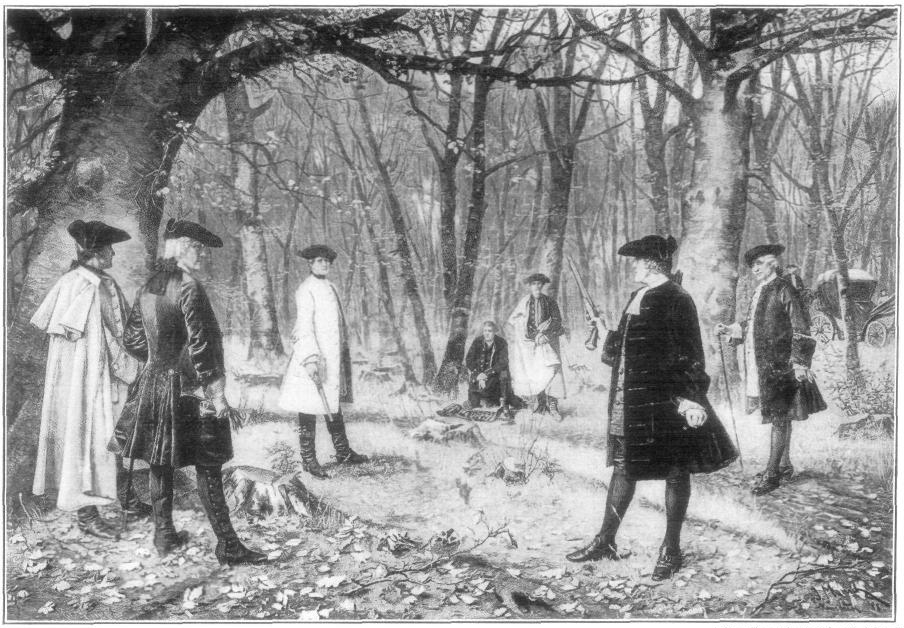

Near the end of his term as VP (July 11, 1804), Burr killed Alexander Hamilton in a duel. When Hamilton died, so did Burr’s hope of ever becoming president. In a desperate bid to revive his political fortunes, Burr looked to the Louisiana Territory, which Jefferson had purchased from France in 1803. The territory was mostly unsettled, and its borders were still disputed by Spain. Given the difficulty of travel in the early 19th century, this part of the country was very isolated and had little contact with the original states of the new republic. This isolation, coupled with the border disputes and recent annexation by the United States, encouraged many of its settlers to consider secession. Burr believed that with the support of a small but well-armed military force he could turn Louisiana into his own empire.

In the summer of 1804, while still vice president, Burr had sent a message to Britain’s Minister to the United States, Anthony Merry,offering to help Britain take the Western territories from the United States. While Merry was in favor of the plan, Britain’s new Foreign Secretary, Charles Fox, found Burr’s request treasonous, and on June 1, 1806, recalled Merry to Britain. Without the support of Britain, began looking for co-conspirators that would help him build a local militia.

Eventually he turned to his old friend General James Wilkinson. Burr used his influence as VP to convince President Jefferson to appoint Wilkinson as the first Territorial Governor of Louisiana and together they made covert plans for Wilkinson to invade and colonize Spanish territory in the West. They also schemed to establish an independent “Empire of the West” on a Napoleonic model. The conspirators even considered invading and annexing Mexico to add to their empire with New Orleans as capital.

When Burr was dropped from the presidential ticket in April 1805 (and after he was acquitted of murdering Hamilton), he headed to Pittsburgh, procured a riverboat and embarked down the Ohio and Mississippi Rivers to New Orleans. Along the way, he recruited a small army (about 150 men). When he arrived in New Orleans in 1806, he was fervently welcomed because of his plans to conquer the Spanish Texas.

As rumors of his plan reached Washington, Jefferson immediately accused Burr of treason. Wilkinson, then turned informant on Burr (to avoid being charged with treason himself) and arrested Burr near Nachez, Mississippi. In May 1807, Burr was tried for treason in front of U.S. Chief Justice John Marshall in the circuit court at Richmond, Virginia (Supreme Court Judges rode the judicial circuit until 1911). This was truly the trial of the century. Ultimately, Burr was acquitted on a technicality. The US Constitution defines treason very specifically: in which Article III, Section III treason is defined as consisting only in the “levying War” against the United States. Justice Marshall insisted on absolute adherence to that strict definition — which Burr’s actions did not meet. Marshal stated that for Burr to be found guilty, the prosecution had to have proven that there had been an “actual use of force” and that Burr was “connected to that use of force.” In effect, Marshall demanded that the government prove what it could not prove.

On September 1, 1807, the verdict was read: “We of the jury say that Aaron Burr is not proved to be guilty under this indictment by any evidence submitted to us. We therefore find him not guilty.” While they had little choice, the members of the jury hinted that they might have decided the case differently had it not been for the Marshall’s instructions.

While Burr was victorious in court, he lost in the court of public opinion. Across America he was burned in effigy. Several states filed additional charges against him, and he lived in fear for his life. Burr fled to Europe, where he tried without success to convince Britain and France to support other North American invasion plots. After four years in exile, Aaron Burr returned to New York in 1812. Burr put up his shingle in New York as an attorney and found ready business. He would live the rest of his life in relative obscurity, his dreams of empire forever undone.

Want to have the

Regimental Brewmeister

at your site or event?

You can hire me.

https://colonialbrewer.com/yes-you-can-hire-me-for-your-event-or-site/